Introduction

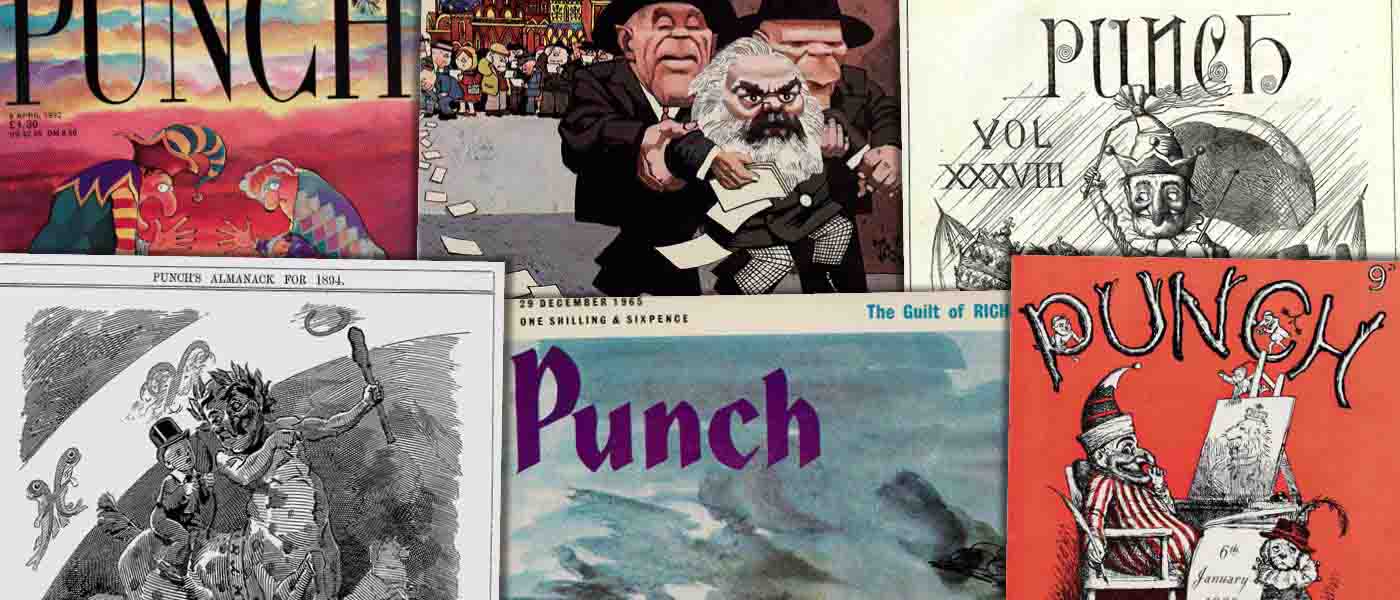

For a long time the Victorian period has popularly been regarded as one in which British cookery slowly declined in quality in the middle- and working-class domestic environment, while French-influenced cuisine triumphed in grand houses, hotels and restaurants. For those who believe this narrative there were inevitable consequences. By the end of the Edwardian period, the aping of French dishes by cooks who didn't fully understand the techniques, working in houses which couldn't quite afford the ingredients, had, if the narrative is to be believed, devalued the general experience of British food to a point where it had become laughable. Many researchers come to the study of Victorian food with this story of decline firmly entrenched, but Punch offers one way in which such views can be challenged.

General Search Terms

One of the most striking things about the Punch Historical Archive is its sheer scope. A general search on common terms such as 'dinner', 'food', 'restaurant', 'eating' or even 'menu', 'bill of fare' or specific foodstuffs such as 'plum pudding' or 'jelly' will yield over a thousand results. It's an excellent way to demonstrate the ubiquity of food and food-as-metaphor in Punch, and through that to widen discussion in a seminar context to the use of food in literary sources. As one of life's few constants (everybody eats), food is widely drawn upon both in Punch and in the wider context of written sources, both fictional and non-fictional, in nineteenth century Britain. Many of Punch's contributors, including, most notably, Thackeray (1840s-50s) and the Grossmiths (1880s), used depictions of food or dining as a means of illustrating certain social characteristics which would have been instantly recognised by their readers, but which are rather harder to grasp 150 years on. For example, Mr Pooter's declaration that he was on the point of leaving for his dinner at 1.30 pm (9 February 1889: 64) immediately marks him out as plebeian, despite his social desires. The upper classes dined in the evenings, usually after 7 pm, and lunched around the time Pooter claims to dine. Throughout The Diary of a Nobody columns, Pooter rarely dines after 5 pm. Such kinds of social distinctions would have been recognised and laughed at in their day, but barely noticed by a modern reader, not alert to the nuances of Victorian eating habits. A researcher intending simply to gain a flavour of the way in which food was used, or the ubiquity of certain foodstuffs or themes could use general search terms such as those above, but it is more useful to search in a more directed manner.

Specific Search Examples

The period covered by the archive is one of huge social change, and the advanced search function, or the use of more specialised search terms, can not only elucidate specific research questions, but also give the researcher a general view of change over time. Examples, and some example searches, include:

Key culinary figures, both in their day, and in historical perspective

Search string, all documents: Delia Smith - in addition to a book review by Smith herself, the view of her as the uber-TV-chef is confirmed in an article of 8 November 1978: 796 where she's mooted to present A Bit Tasteless, telling viewers how to get the best out of all the shows she is not in.

Etiquette for eating out and dinners at home

Search string, all documents: restaurant + search within: fork. Article called 'In the time of the restauration', which immediately draws the eye, and contains not only a glimpse at (incorrect) table manners, but also hints at pre-theatre habits, prices and expectations (8 December 1883:273).

Restaurants, especially identifying fashionable examples (predominantly in London)

Search string: restaurants, search within: ladies, plus date limiter of 1919-1939 (aiming to tease out changes due to increasing visibility of women, post-war). Lengthy satire of the habit of ladies opening restaurants with no experience (26 April 1922: 334).

Contrasting views of British and foreign food

Search string: restaurant + search within results: Paris yields a lovely contrast between writer expectations - elegant restaurants and dining alone, and being dragged around his English friends' houses eating endless mutton (3 March 1849: 92).

Food abroad in general, especially in France and other tourist destinations

Historical viewpoints on food and dining, i.e. the rejection by Victorians of earlier foods, and the equal rejection by twentieth century commentators of Victorian food; Specific diets, e.g. of the Irish (particularly leading up to the Great Famine of the 1840s), the working poor; Food adulteration (especially of concern c.1840-1914).

Diets and dieting, especially in the twentieth century, but from the 1880s

Some trends or themes, such as eating horsemeat (there was a brief attempt to promote it in the mid- nineteenth century), vegetarianism and veganism (post 1940)

Direct comparisons between attitudes today and at points in the past, e.g. fusion food

Domestic service, the 'servant problem' and changing views of cooks. This area is especially significant for studying gender-related questions in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Search string, all documents: servants + cooks. Evocative list of things a cook should do (being, of course, a list of things a cook really should not do) 26 July 1845: 45. This article follows in a long- established satirical vein, starting with Jonathan Swift's Directions to Servants, which is longer, but similar, in advising servants wrongly. It's a good list of things deemed unacceptable, but which therefore presumably were fairly common.

In order to demonstrate fully the way in which the Punch Historical Archive can be used, I've taken one example, in this case that of key culinary figures, and queried the archive using various search terms, detailed here:

Investigating Leading Chefs of the Mid-Nineteenth Century. My starting point was to take a selection of cookery book writers working in the period 1840-1860, and use their names as search strings. All should be known to any researcher working in nineteenth century food, even at a fairly basic level. The below analysis concentrates on one man, Alexis Soyer; the most cited chef in the database.

Alexis Soyer (1810-1858) was the chef at the Reform Club, a social reformer through the medium of food, and an indefatigable self-publicist. The Times, on his death, published a series of articles suggesting he was a true great, mainly for his work in the Crimea, where his various reforms, and indeed the invention of the Soyer Stove, remained the backbone of armed forces catering until well into the twentieth century. He was the best- known culinary figure of Britain in the 1840s-50s, and published a series of cookery books aiming at different social classes. Today, he is largely forgotten.

The search string 'Soyer' (whole document, no limiters) in the Punch Historical Archive yields 124 results, from 1844 to 1988. The entries up to his death fall into these categories: use of his name only, in which context it is shorthand for the most high-end cuisine of the day; direct accounts of his work or of his dishes, usually lampooned, especially as they are invariably in French and therefore open to Punch's interpretation (thus, a dish à la Nelson must not include a white feather, etc.); and, increasingly after his work in the Crimea, reference to him in more positive terms, usually in contrast to another figure or policy. A lengthy poem was published on his death which, like the various references in The Times, concentrates on his military work, and does not dwell on his talent for self-publicity, in contrast to a number of earlier articles.

The rapid decline of Soyer as a household name can then be charted very graphically through the references after his death, dwindling from a yearly mention, to once-a-decade in the middle of the twentieth century. By the 1960s he is of historical interest only, and the last mention of his name is simply a reprint of a cartoon from 1850 for a caption competition.

In this way the Punch Historical Archive can be used not only to glean information on how Soyer was regarded at the time, but also on the way posterity has treated him. In contrast, there are no mentions of Mrs Beeton during her lifetime, but increasing numbers from 1902, when the revised, corrected and rather more reliable new edition of the Book of Household Management was issued. The habit of regarding Beeton as the most famous cook of her day, and a symbol of the nineteenth century is entirely belied by a close search of the Punch database.

Other searches based on names show a bias toward male chefs. Francatelli, Ude, Careme and Escoffier are all represented, while Agnes Marshall, who was a contemporary of Escoffier, and a leading writer of her day, is not. Maria Rundell, an extremely popular early nineteenth century author, contemporary with Ude and Careme, is cited, as is Hannah Glasse, who was the best-selling author of the Georgian period, but not to the extent of their male compatriots. Those cooks who were dead by the time of writing (all of those named above, except Francatelli), are used as shorthand for great cooking; in the case of Rundell, great home cooking. Francatelli, as with Soyer, also comes in for some direct comment, including a poem (14 November 1857: 197), and a pun on the state of his potatoes ('to be mixed by mash-inery' 1 January 1864, Almanack: np). The database therefore needs to be used alongside sales figures and later scholarship on cookery books, and also requires an awareness of the middle class and predominantly male readership of Punch at the time. Some articles form a useful corrective to general assumptions, however, as a search for Mrs de Salis throws up a fairly searing condemnation of her Tempting Dishes for Small Incomes (6 September 1890: 113), which is rather at odds with her own views, as expressed in the title.

Contextualising the Results

Punch was a fast-moving, up-to-date publication, which commented not just on the big news stories of its day, but also the lesser known items, along with general trends. References to, for example, Mrs Griffin's Establishment for Young Ladies (27 February 1847: 87), make little sense unless the reader happens to be familiar with the lesser-known works of Dickens. A general internet search often clarifies some of the references, if they are picked up, but researchers should also be aware of Gale Historical Newspapers, in particular The Times Digital Archive (see the essay by Gary Simons on this site). Inevitably, the more a researcher knows about the background to the period, the more easily some of the references can be understood, and it's important to remember when using the archive that Punch was humorous and satirical. Too often, statements can be taken out of context and repeated as fact: the oft-repeated story of prudish Victorians covering the table legs being a good example.

Potential for Teaching

The Punch Historical Archive is an excellent social history resource. At its most basic level, it should serve as a reminder that people in the past had a sense of humour (often forgotten in the heat of research). Many of Punch's early writers drew on a vast range of classical and contemporary knowledge which is often lost to most modern scholars, so it is a good starting point to encourage students to seek out contextualising information. In the field of food history, it's a way of elucidating the contemporary meanings given to specific foodstuffs, and of examining the way in which chefs, cooks, writers, restaurants and types of meal were regarded at a given point in time. Food is so ubiquitous that it is sometimes hard to see it as a metaphor or signalling device.

The usefulness of Punch is that it makes such a usage obvious. Care needs to be taken not to be overwhelmed by the amount of food references, as the Punch Historical Archive illustrates graphically the interest in food across the whole period covered by Punch, and search strings need to be well chosen. Overall, however, it should be considered a vital tool for appreciating the ephemerality of food and the meanings associated with it.

CITATION: Grey, Annie: "Food in Punch: Representations of Culinary Culture." Punch Historical Archive 1841-1992. Cengage Learning 2014