The electoral college is a group of electors, outlined and defined in the United States Constitution, established for the purpose of electing the president and vice-president. Read the overview below to gain an understanding of the process and explore the previews of opinion articles that highlight diverging views on this voting system.

"Electoral College." Gale Opposing Viewpoints Online Collection, Gale, 2021.

The United States Electoral College is a deliberative body through which the US president is elected to office. The Electoral College has 538 electors; each state has a set number of electors equivalent to its two US senators plus its number of US congressional house representatives. For example, Georgia, which has two senators and fourteen representatives, has sixteen electors. The state with the most electors is California, which has fifty-five. The District of Columbia has three electors.

Though voters may be unaware of the process, when they cast their ballots during the general election in November, their votes do not directly elect the president, but instead decide how the electors from their state will vote. The winner of the popular vote in each state, based on the number of actual votes cast by the general population in that state, is determined. The electors for each state are generally obligated to vote for that candidate, therefore all of a state's electoral votes tend to go to the same candidate. A candidate can win the popular vote of the United States but not the presidency if the candidate fails to gain the majority of electoral votes. The winning candidate must receive at least 270 electoral votes to win the presidency. On the first Monday after the second Wednesday in December of the election year, the electors assemble in their respective states to cast their ballots and elect the president.

The Electoral College exists because of a compromise reached during the Constitutional Convention in 1787. During the convention, delegates considered several different ways of electing the president but could not agree. The issue was sent to the Committee of Eleven on Postponed Matters, which was developed to work on difficult issues facing the convention. The committee proposed the system of electors. Originally, the electors would each cast two votes. The candidate with the greatest number of votes would become the president. The candidate who came in second would become the vice president. Electors were not permitted to select two candidates from their own state.

The compromise was accepted because it solved three problems. First, it created a buffer between state and federal governments. Second, it protected the election from undue influence from the more populated states. Third, it gave citizens some input into the election of the president while also addressing concerns held by several founders that common voters could be easily manipulated into electing unqualified candidates. Some of the delegates feared that citizens would not have confidence in a president if they were too far removed from the election process. To help allay fears that the federal government had too much control over presidential elections, each state decided independently how to choose its electors.

After the election of 1800, Congress revised the design of the Electoral College. In that election, Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr received an equal number of electoral votes. The election went to the House of Representatives after the Senate established that there was a tie. The House, however, had to vote thirty-six times before Jefferson received the majority of votes and was named president. The Electoral College's original designers had not anticipated a tie, especially not one between candidates of opposing parties.To remedy this, in 1804 Congress ratified the Twelfth Amendment, which established that each elector would cast a single vote for president and a second single vote for vice president. If no candidate received a majority of the votes, the House of Representatives would choose from the top three candidates. The Senate would choose the vice president from the top two candidates in the case of a tie. Since the ratification of the Twelfth Amendment, only one other constitutional revision has been made to the electoral process. In 1961 the Twenty-Third Amendment granted the District of Columbia the same number of electoral as the least populated states, which has remained three electoral votes since the amendment went into effect. No further attempts to reform, amend, or abolish the Electoral College system have yet been successful.

Since 1836 most states have assigned electors based on the results of the states' respective general elections. Thus, electors typically vote for the winner of the state popular vote. Maine and Nebraska are the only two states that do not follow a winner-takes-all approach in which the candidate with the most votes receives all of the state's electoral votes. In practice, electors vote for the candidate who wins the popular vote in their state however several states do not require this. A federal court ruled in August 2019 that members of the Electoral College are not mandated to vote for the winner of their state's popular vote. This was a win for faithless electors, which are Electoral College delegates who refuse to cast their votes for the presidential candidate their state has pledged to support. However, in July 2020 the US Supreme Court ruled that states do have the authority to require electors to vote for the state's selected candidate for president as determined by the results of the popular vote. This Supreme Court ruling affirmed the power of states, not individual electors, to assign electoral votes.

Instances have occurred in which the assignment of electors has created challenges in contested elections. In 2000, for example, a dispute over the results of the popular vote in Florida continued for a month after the general election and ultimately reached the US Supreme Court. The court's ruling halted an ongoing recount in the state and allowed Florida's secretary of state to certify the existing election results, which awarded twenty-five electoral votes to Republican candidate George W. Bush. Florida's votes pushed Bush's total electoral votes to 271, enough to win the presidency. Democratic candidate Al Gore won the national popular vote by 543,895 but lost the electoral vote by just five electors because he lost the popular vote in Florida by an estimated 537 votes—less than 0.01 percent of total votes cast nationwide.

The winner-takes-all approach of most states has led to the phenomenon of swing states. Swing states are states in which the popular vote is determined by a very narrow margin. In 2016 swing states were key to Donald Trump's unexpected victory against Hillary Clinton. Though he lost the national popular vote by 2.9 million, and Clinton won 48 percent of the overall US popular vote while Trump won 45.9 percent, Trump gained 304 Electoral College votes by capitalizing on narrow wins in swing states. Trump won Michigan by less than 1 percent to gain sixteen electoral votes, Wisconsin by 1 percent to gain ten electoral votes, and Pennsylvania by 1.2 percent to gain twenty electoral votes. According to an analysis published in U.S. News & World Report, Trump's success depended largely on his ability to win in a number of previously Democratic states by very small margins. While former US president Barack Obama won two states by 2 percent or less in 2012, Trump won six states by 2 percent or less in 2016.

In 2020 Trump contested the results of the presidential election after losing to Democratic candidate Joe Biden. Biden won five swing states by 2 percent or less, but also won the US popular vote by more than 7 million, taking 51.3 percent of the popular vote to Trump's 46.8 percent. Biden won 306 electoral college votes, surpassing the 270 votes needed to become president and Trump's 232 votes. Trump's campaign filed dozens of lawsuits in several battleground states including Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Nevada, and Pennsylvania due to claims of widespread voter fraud, constraints on poll observers, and illegal extensions on deadlines for mail-in voters. These lawsuits were an effort to block the secretaries of state from certifying results and deny Biden the electoral votes needed to win the presidency. Despite the Trump campaign's claims of widespread irregularities, the campaign failed to produce sufficient evidence, and the dozens of lawsuits, including one to the Supreme Court, were dismissed. In addition, election officials and state governors in every state Trump contested, including Republicans, stated there had been no evidence of widespread election fraud.

By January 1, 2021, Trump still had not formally conceded the election and continued to dispute the results. Fourteen Republicans in the US Senate and more than half of the Republican members of the US House stated they would contest the Electoral College votes from battleground states, including Arizona and Pennsylvania. Republican Majority leader Mitch McConnell and others advised against the tactic, stating it would not change the results of the election. On January 6, as the US Congress met in a joint session to certify Joe Biden's 2020 election win, President Donald Trump held a rally in which he continued to falsely dispute the election results and encouraged his followers to march on the Capitol. A pro-Trump mob then stormed and breached the US Capitol. In the chaos, Congress was evacuated, and several police officers were injured; one later died from his injuries. A rioter was killed by Capitol police, and three rioters died from other causes. The Capitol was eventually cleared of the rioters, and Congress reconvened, working late into the night and the following morning to certify the remaining electoral college votes. There were calls for the use of the 25th Amendment by Vice President Mike Pence and Trump's Cabinet to remove him from power or for his impeachment. The House began proceedings to impeach Trump on January 13, 2021, after Pence declined to invoke the 25th Amendment.

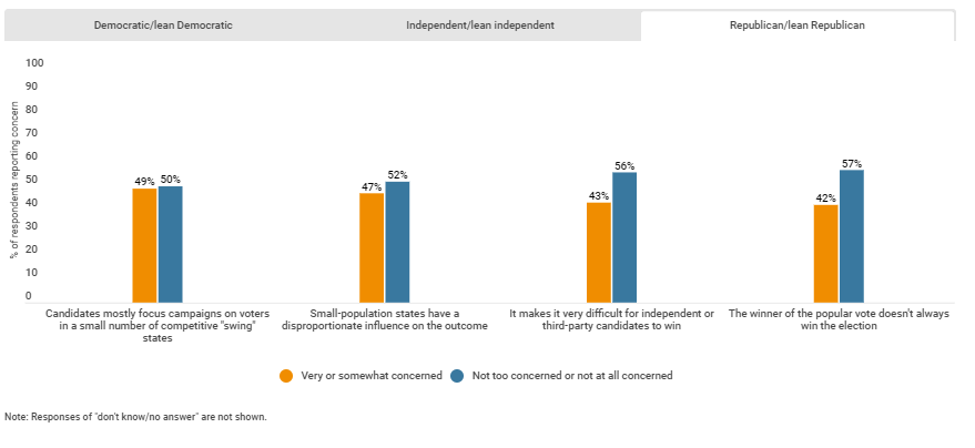

When the Electoral College was created, James Madison hoped it would avoid the silencing of minority opinions by an overly influential majority. Madison worried that factions might arise within the country that would harm the nation as a whole. He believed that these factions could be kept in check by making the election of the president representative rather than direct. For those who support the Electoral College, the system is crucial to maintaining the rights of individual states, specifically states with smaller populations. Defenders argue that the Electoral College system stabilizes the nation and prevents big city populations from dominating national elections.

Those who oppose the Electoral College system disagree with Madison's reasoning and argue that a system of direct voting reflecting the will of the majority of voters is a better system for electing a president. Such critics question whether the Electoral College results are truly representative of the people. In five elections in US history—1824, 1876, 1888, 2000, and 2016—candidates who won the popular vote did not win the presidency because they failed to gain a majority of electoral votes. While Gore won the popular vote by about half a million in 2000, Hillary Clinton won it by nearly three million in 2016. That year, Trump lost the popular vote by the biggest margin of any other US president who in turn won the Electoral College and the presidency. The disparity led to calls to abolish or reform the Electoral College.

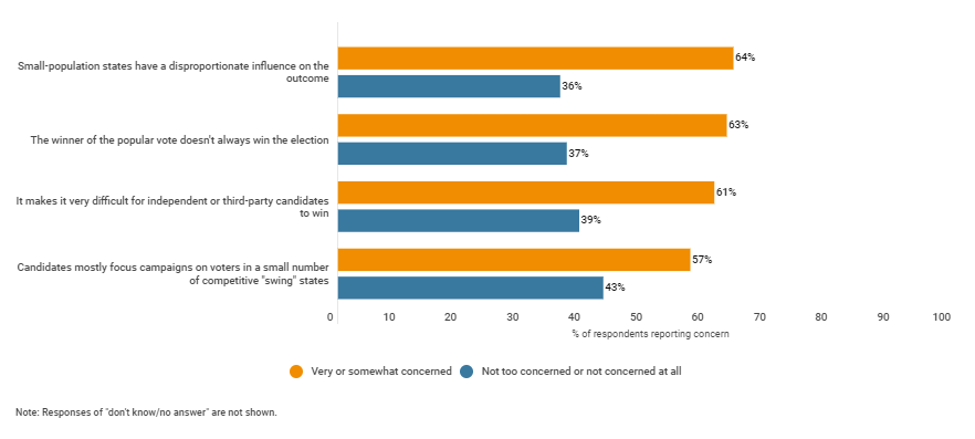

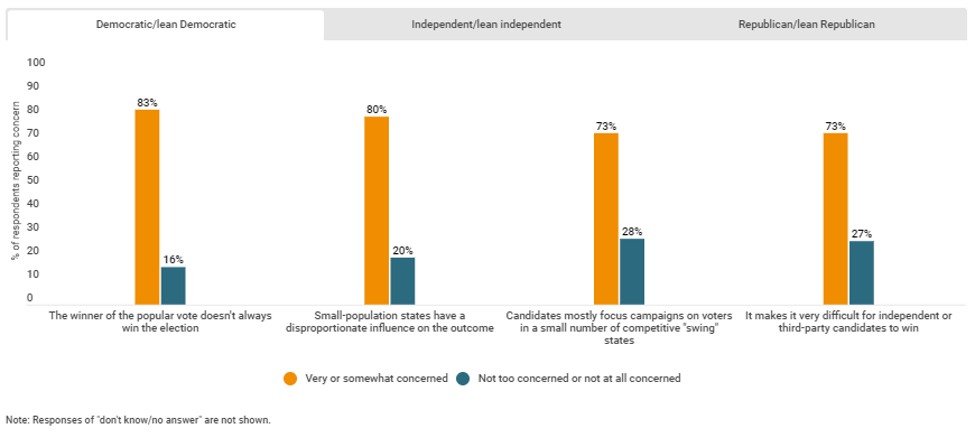

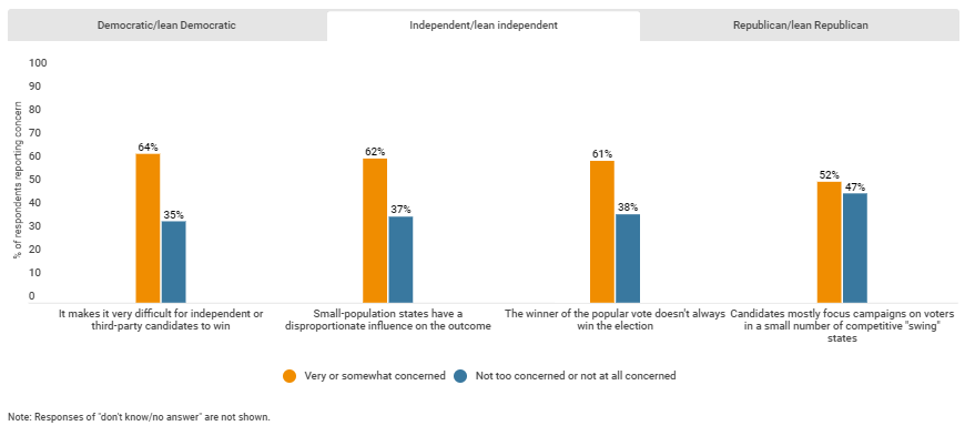

Critics also point to swing states as an example of why the process does not truly represent the will of the voters. Many political analysts, politicians, and voters have asserted that candidates often focus their time, money, and effort on only a few swing states. Meanwhile, they argue, candidates pay little attention to those states that have a history of always supporting the Democratic or Republican candidate, thus ignoring the individual interests of many voters. According to a September 2020 Gallup poll, 61 percent of voters surveyed indicated a preference for the national popular vote over the Electoral College, while 38 percent preferred the Electoral College.

Following the 2000 presidential election, the National Popular Vote (NPV) Interstate Compact initiative emerged as a potential solution, and it has regained popularity in the wake of the 2016 election. States that adopt the initiative agree to apportion their Electoral College votes to the national popular vote winner rather than their state's popular vote winner. The plan requires the participation of enough states to reach the threshold of 270 electors before it can go into effect. As of November 2020, fifteen states and the District of Columbia, representing a total of 196 Electoral College votes, have joined the compact. Five of the fifteen participating states have signed on just since 2018. While the NPV model has gained traction, a 2019 Gallup poll suggests that the public prefers a different approach: 55 percent of US adults polled supported amending the Constitution to base the winner on the national popular vote, while just 45 percent supported the NPV model.

This article offers a history of the Electoral College, including a serious effort in 1969 to eliminate it from the electoral process. The author argues that the College has never functioned as the framers of the Constitution intended and in practice favors some states over others in determining the winner of presidential elections. Various potential solutions to the problems the College creates are discussed, including the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact formed in response to the 2000 election, in which fifteen states and the District of Columbia agree to assign their electoral votes to the candidate who wins the popular vote.

Author Joseph Connor considers the origins of the Electoral College and various attempts throughout the history of the United States to reform it. In addition, he discusses individual presidential elections contested as the result of discrepancies between the popular and Electoral College votes.

This article discusses the Electoral College, its history, and the pros and cons of keeping it in place.

Source: "Americans Split on Proposals for Popular Vote." Gallup, Mar 14, 2019. Tribune Content Agency Graphics. https://news.gallup.com/poll/257594/americans-split-proposals-popular-vote.aspx (accessed November 4, 2019).

COPYRIGHT 2020 Gale, a Cengage Company.