The American Revolution was a civil war in every sense of the word, a fratricidal conflict that divided men and women throughout the Empire, in Britain no less than the American colonies. For the metropolitan public, however, the American Revolution was a very different war from the one experienced by Britons in America. Despite the mounting burdens of taxation, military service, and economic loss, most Britons participated in the American Revolution at one remove. For this reason alone, newspapers were an important factor in the internal divisions that beset Britain during the 1770s and 1780s, conveying information, shaping opinion and—often—fomenting controversy.

Government and Opposition

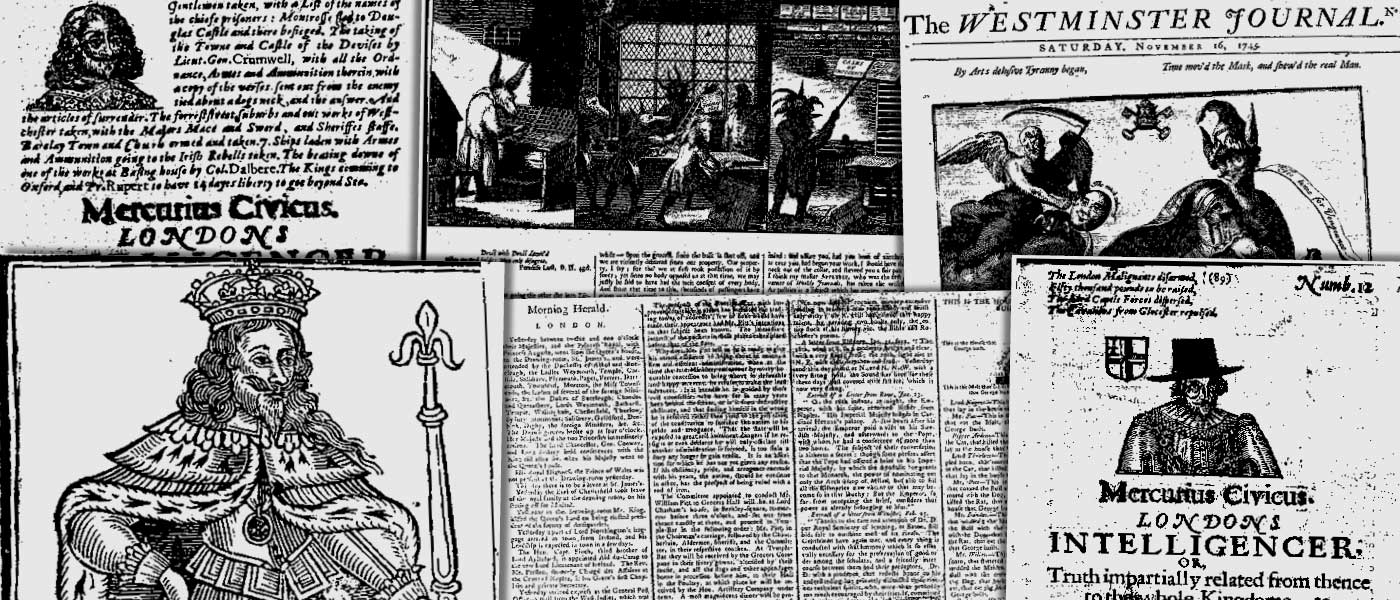

Supporters and opponents of Frederick North's ministry were well aware of the importance of the press. In the late 1770s, there were nearly 35,000 newspapers in daily circulation in England, meaning that the reading public may have included as many as one in six adults. Throughout the war, partisans on both sides sought to turn this influence to their advantage, publishing petitions and addresses in the London and provincial press (notably during the summer and autumn of 1775), writing essays supporting or denouncing the government's management of the war, and attempting to control the way that newspapers reported events such as the County Association meetings of 1780. Often, the editors and proprietors of individual papers helped fan such differences of opinion. Under the editorship of Henry Bate Dudley, the Morning Post was a generally reliable pro-ministerial outlet; the London Evening Post and the General Advertiser, on the other hand, tended to side with the opposition. During the intense press coverage that greeted the court-martial of Admiral Keppel in 1779, all three papers sought to provide what William Parker of the General Advertiser called 'impartial and authentick intelligence' of the trial's proceedings, yet they also divided along predictable party lines in defending or attacking the famously (or notoriously) pro-American admiral.

Parliamentary Reporting

Despite such partisan divisions, the American Revolution witnessed a gradual decline in the acrimony that had long characterized relations between the government and the press. Following the House of Commons' failed prosecution of eight London printers in 1771, the government tacitly agreed to allow newspapers to publish parliamentary debates. Because visitors in both houses of Parliament were prohibited from taking notes until 1783, such reports were necessarily based on the recollections of newspapermen such as the Morning Chronicle's William "Memory" Woodfall rather than written transcriptions, and during especially sensitive debates, including those on America in 1774, the government insisted on clearing the galleries. Still, the newspaper publication of parliamentary debates became sufficiently routine for printers to contact politicians directly with requests for accurate information. On several occasions during the early 1780s, the Morning Chronicle published speeches and other information that Woodfall had received from the treasurer of the ordinance William Adam. In a letter to Secretary at War Charles Jenkinson requesting an official copy of the army estimates for 1780, Woodfall hoped that Jenkinson would agree that it was better to publish the correct account of a matter that 'by the mistake of a single figure might be grossly perverted'. Woodfall also noted that a rival, John Almon, had promised to publish an 'exact account' of the estimates in the London Courant,presumably based on a communication that Almon had received from Jenkinson's office (Woodfall to Jenkinson, 9 Dec 1779, British Library Add MSS 38,212, f. 274).

The War in America

Unlike news of events in Parliament and Britain's provincial cities, newspaper reports from America inevitably depended on second (or, at times, third) hand accounts. In cases where more than one set of participants had access to metropolitan printers—the British merchants whom Admiral Rodney plundered after taking the Dutch Caribbean island of St Eustatius in 1781 are a good example—such reports could be critical of the government. Often, however, coverage of the war in America was one-sided in the government's favour. In the notorious case of Banastre Tarleton, whose brutal tactics in the Carolinas and Virginia earned him the enmity of Americans everywhere (including the future US president Andrew Jackson), the coverage was overwhelmingly favourable and consisted mainly of laudatory dispatches from Tarleton's military superiors, Sir Henry Clinton and Lord Cornwallis. When Tarleton returned to England in 1782, he received a hero's welcome.

Anti-Americanism

Similar biases were evident in the treatment that the British press accorded American patriots and the patriot cause. Although George Washington managed to transcend partisan differences, with even the pro-ministerial Critical Review admitting in 1779 to a 'high opinion' of the American general, the image of rank-and-file patriots was usually less generous. In reporting on the commencement of hostilities in 1775, many papers carried lurid accounts of rebel atrocities, leading to allegations that the British government was using the 'utmost industry. . .to inflame men's minds' against the Americans (anonymous letter to Robert Carter Nicholas, 22 Sept 1775, National Archives, CO 5/40/1, 22). With the outbreak of war with France and the North ministry's implicit recognition of American grievances in the Carlisle Peace Commission of 1778, the ministerial press moderated its tone, yet even the coming of peace did not dispel the impression of partiality. As Thomas Jefferson complained in a 1784 letter to the Netherlands Leiden Gazette, many Europeans turned to British newspapers for information about America; all too often, what they found was neither fair nor accurate (Merrill D. Peterson, ed., Thomas Jefferson, Writings [New York, 1984], 571-4).

Gazettes to the World

If Jefferson's words remind us of the partisanship of British newspapers, they also highlight the growing power and influence of the periodical press—an influence, moreover, that increasingly reached beyond Britain's borders. Even as Americans lamented the national biases of Britain's newspapers, much of the foreign news that appeared in American newspapers was based on stories that had first appeared in the British press. Significantly, British newspapers played a major role in the imperial humanitarianism that swept Britain in the Revolution's wake, keeping the plight of British India before an outraged public and building support on both sides of the Atlantic for the eventual abolition of the slave trade. Although not the only structure of power in late-Georgian Britain, the newspaper press was increasingly among the more important.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Barker, Hannah. Newspapers, Politics, and Public Opinion in Late Eighteenth-century England (Oxford, 1998).

Brewer, John. Party Ideology and Popular Politics at the Accession of George III (Cambridge, 1976).

Bickham, Troy O. "Sympathizing with Sedition? George Washington, the British Press, and British Attitudes during the American War of Independence," William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd ser., 59, 1 (2002): 101-122.

Conway, Stephen. The British Isles and the War of American Independence (Oxford, 2000).

Gould, Eliga H. The Persistence of Empire: British Political Culture in the Age of the American Revolution (Chapel Hill, N.C., 2000).

Rodgers, Nicholas. "The Dynamic of News in Britain during the American War: The Case of Admiral Keppel," Parliamentary History, 25, 1 (2006): 49-67.

CITATION: Gould, Eliga H.: "The American Revolution." 17th and 18th Century Burney Newspapers Collection. Detroit: Gale, 2007.