Introduction: Interpreting Content

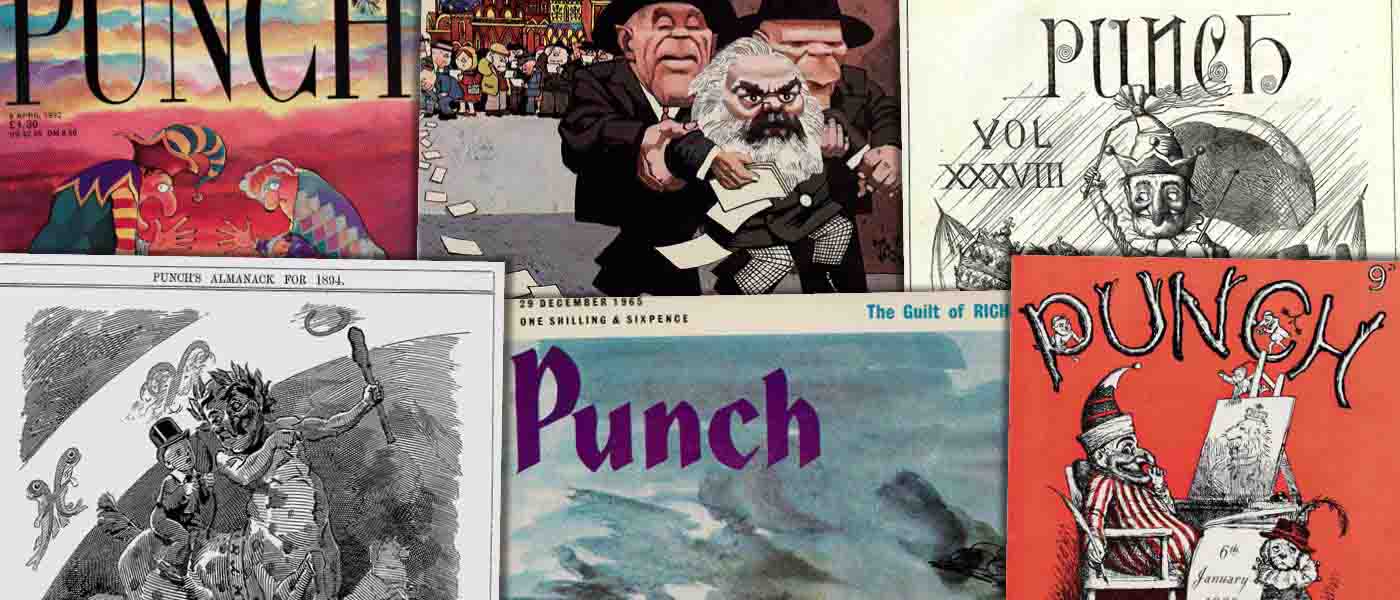

In the first half of the nineteenth century graphic satire was transformed by changes to printing practices. During this time it became fast, easy and affordable for businesses to print textual and graphic elements together and en masse. Such an increased opportunity for the inclusion of images in texts changed how we 'read' visual evidence. For, compared with the graphic satires printed and sold as individual sheets that were dominant in mid- to late-Georgian England, graphic satires published alongside text and inside publications - such as Punch cartoons - were rich in printed context. Text of this kind is valuable when reading Punch cartoons and when searching for Punch cartoons in collections such the Punch Historical Archive. And yet, we should be cautious of allowing textual contexts to overwhelm the graphic, of being subsumed by readings that rely on accompanying text, of seeing such text as the only context through which Punch cartoons are read.

This case study will explore how students can make, as far as is possible, non-textual readings of Punch cartoons and the value of doing so. The starting point is that each Punch cartoon communicated using a complex non-textual interplay between cultural referents and shared language. To interpret a design, to 'get the joke', contemporaries would have needed this contextual knowledge - of major events, well-known individuals, widely circulated texts; and for artists to retain an audience, they would have needed to remain attentive to what their audience knew. This mode of communication made Punch cartoons a powerful form that could transcend text, summarise complex ideas, and say what could not be said without explicitly saying it. In turn, the necessity to interpret, to understand, makes Punch cartoons challenging for the student researcher to read because before an interpretation is made they need to acquire knowledge of cultural referents and shared language, of context. The text around an image might seem an obvious place to begin, but this sort of reading limits research to interpretations based on the context their creator(s) intended them to be read in. It is important to move beyond these limitations because readers' uses of media are (and were) inherently individual: we glance, we read carefully, we navigate in non-linear ways, we discuss snapshots with friends, we cut out sections we enjoy to repurpose, remix and reuse in new contexts. These experiences may be impossible to replicate from the source media alone, but forcing oneself to read Punch cartoons for themselves does at least make it possible to keep within scope the many possible ways in which they were read and received.

The Almanack as the Gateway to Punch

This case study uses cartoons from the Punch Almanack, the first true commercial success to carry the Punch name. Released for the 1841 Christmas season it sold around 90,000 copies in a single week. This proved a launch pad for the fledging Punch and a mainstay in its calendar with sales regularly in excess of 150,000 - a figure largely untroubled by the fluctuating circulation of the weekly. It would continue to be published into the 1960s. The Punch Almanack followed a long tradition of almanacs published to coincide with the New Year. As was the case with most almanacs, the Punch Almanack was a miscellany that included a calendar and predictions for the year ahead. However in the Punch version humour was preferred to earnest astrological readings and the type of humour chosen intended to appeal beyond the core London audience the Punch weekly enjoyed, often drawing on the traditions of Regency caricature to satisfy a well-established readership. It was appropriate then that in the early- to mid-Victorian period the Punch Almanack would return time and again to a classic of English comedy: the relationship between English town and countryside.

Researching a Topic

The Punch Historical Archive enables for the first time full search of the Punch Almanack. To search the Punch Historical Archive for cartoons on the topic town and country, first select the 'Advanced Search' interface. Enter 'town' and 'country' in the search boxes provided and make sure the tab between them on the left hand side is set to 'and'. This ensures the return of all records where the words 'town' and 'country' are included. To refine the results further navigate to the 'Limit Results by' section and tick both 'Almanacks' and 'Cartoons'. Finally, to keep the results set manageable, specify a time range by changing the values in the 'Limit Results by Publication Dates(s)' section. Searching between 1850 and 1870 will return over one hundred results. It is important to note that this search is based on the textual elements - titles, captions and articles - that surround Punch cartoons; the search does not search the images themselves. Therefore to truly research a topic for a class or an essay using Punch cartoons, a student will need to use these search results as a starting point for further investigation - the 'View Page' and 'Browse Issue' options alongside each search result allow he or she to begin browsing in this way.

Returning to mid-Victorian cartoons on town and country, this search returns many useful results that enable users to explore and to offer preliminary interpretations of the topic at hand. In the 1853 Punch Almanack we find the reality of country life - of farming, cattle, dirt, hens - too challenging for an uncomfortable Londoner dressed in top hat, cravat and a tailored suit. His rural companion, on the contrary, is relaxed, amiable and dressed in simple clothing. Both men are Britons but their idea of what constitutes comfortable living are very different. On the same page, a second design presents the sort of country ideal this Londoner might have expected to find. Trees, hedgerow and open space replace quagmire, confinement and productivity. Here a man on horseback, dressed for the country though potentially not of the country, drinks lazily from a flask as he approaches a stile. This, it appears, needs undue assessment to traverse, for his horse is more than capable of the task. And so 'stile' is punned with 'style', an interpretation of country attire that he proclaims 'requires a good deal of judgment'.

Ensuing editions of the Punch Almanack continued to examine the country idyll. In the 1855 edition a cartoon entitled 'Country Races' focused on a gentleman rider. His paunch and gaudy apparel contrasts with the slim and plain-dressed professional behind him, whose horse looks in sympathy at his tired, overburdened equine friend. Whether this was intended to tease at town and country differences, or might have been interpreted as so by the reader, is debatable. The 1860 Punch Almanack shows a new kind of buck, on this occasion in the country on a hunt, replete with a slim hat, pale jacket and check trousers. This is certainly not hunting attire but attire affected for the country by a Cockney ill-suited to its pleasures and pastimes. The following year, a cartoon in the Punch Almanack shows a scenic rural idyll and a countryphile as he attempts to ride a bucking horse. In doing so he loses his top hat and belongings, he is disrobed and emasculated; to this his country friend in a short rounded hat shows little obvious concern. This style of hat returns in the 1862 Punch Almanack, worn here by town dwellers heading to the country and sporting the country look for the new season. Unfortunately having perhaps attended to their appearance rather than practical concerns, or merely having been thwarted by the vagaries of the railways, their horses have been taken to York, to a place they are not. As the comic punchline of this fable states: 'Hunting from Town - it is safer to go with your animal'. The narrative of how urban countryphiles found life beyond the town, often - comically - going about their business with little success, played out slowly, over decades rather than weeks in the Punch Almanack.

Each of the cartoons I have used to tell this story, chosen - it should be remembered - from a search for the words 'town' and 'country' in the Punch Almanack, is gentle, approachable, and uses captions to guide the reader rather than force an interpretation; few signposts constrain the reader's imagination. Even where the 'country' starts and the 'town' ends, and vice versa, is left for the reader to decide. As a consequence, in each of these scenes 'town' and 'country' could be reapplied to a reader's local surroundings, to any two known places delimited by being or not being comparatively urban or rural. And so these cartoons were ambiguous by design, opening up multiple layers of potential interpretation for the contemporary reader and present day student alike.

Conclusion

Of course surrounding text is a vitally important context for understanding both Punch cartoons and their place in societal discourse. This essay merely argues that reading Punch cartoons through Punch articles in the first instance can deny a student researcher at the beginning of his enquiries access to the full range of perspectives from which mid-Victorians read those cartoons. As this essay has demonstrated, this approach can only take us so far. For it is the student's task to supplement these readings and preliminary interpretations with further research, both of visual and textual sources, of contemporary socio-cultural contexts and the histories of caricature and comic art that underpinned so many Punch cartoons.

These investigations can in time close off and open up avenues of enquiry into the contemporary experience of Punch cartoons. For example, a design from the 1866 Punch Almanack might complicate the narrative that town and country were always in opposition. In this cartoon, one Count De St Amaranthe stands on his horse as it vaults a fence. A mix of urban and rural dwellers observe the Parisian. The Count's attire - a short coat, a crested hat and high boots - is as distinct from their own as his actions. He is presented as alien, as outlandish, a crude device that perhaps had the effect of reminding town and country readers alike that for all that divided them, for all that Punch had suggested divided them, that they in fact enjoyed plenty in common. To establish whether this visual discourse was emergent, long-standing, or marginal, and to deepen understanding of contemporary responses to this change of tone, were it one at all, would require further research in and beyond the Punch Historical Archive.

FURTHER READING

Burke, Peter, Eyewitnessing: the uses of images as historical evidence (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 2001)

Gombrich, Ernst, Meditations on a Hobby Horse, and Other Essays on the Theory of Art (London: Phaidon Publishers, 1963)

Miller, Henry, 'The problem with Punch', Historical Research 82:216 (2009)

Leary, Patrick, The Punch Brotherhood : table talk and print culture in Mid-Victorian London (London: The British Library Board, 2010)

Maidment, Brian, Comedy, Caricature and the Social Order 1820-1850 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2013)

Scully, Richard and Quartly, Marian, Drawing the Line: Using Cartoons as Historical Evidence (Sydney: Monash University ePress, 2009)

CITATION: Baker, James: "Working with Visual Evidence: 'Reading' Punch Cartoons." Punch Historical Archive 1841-1992. Cengage Learning 2014