'...to keep continually before the eye of the world a living and moving panorama of all its actions and influences'

A Revolution in News

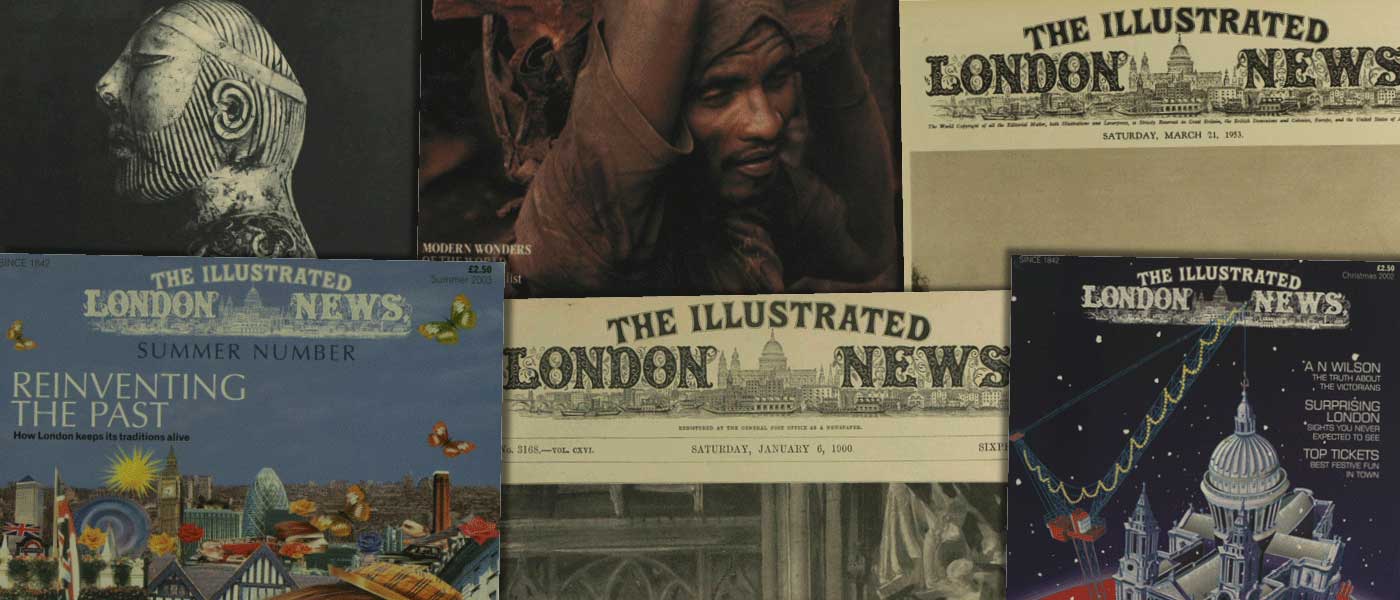

On the 14 of May, 1842, The Illustrated London News burst upon a world that had never seen anything quite like it. Not that there hadn’t been plenty of pictures circulating in one form or another, from crude woodcuts on broadsides to pictures of an animal or a machine in the strenuously “improving” Penny Cyclopedia, to a smudgy portrait in a cheap news-sheet of a notorious murderer. Yet most newspaper readers continued to read long speeches by famous politicians without any glimmer of what the speakers themselves actually looked like, and to follow the news of distant wars and disasters and discoveries with no mental picture of these places beyond what could be imagined from prosy descriptions. The electric, transforming combination of news with images had barely been attempted, and the results had been occasional and sporadic – a conflagration here, a murder there.

The Illustrated London News changed all that forever, from the very first issue. For sixpence, readers acquired sixteen pages covered with thirty-two woodcuts, large and small, accompanying forty-eight columns of news. They saw the fire that had just that week consumed the ancient city of Hamburg, samples of the latest fashions from Paris, young Queen Victoria presiding over a fancy-dress ball at Buckingham Palace, and a myriad of smaller cuts, the whole prefaced with a magnificent view of the London skyline from the Thames, St. Paul’s towering above as the barges of the Lord Mayor’s procession glide past in the foreground. Both the masthead and the lively mix of topics would remain characteristic of the paper for the rest of the century, and beyond. What ultimately most distinguished the Illustrated London News from its predecessors was not just the first issue, or any other issue, but the steady, week-by-week coverage in which pictures fully partnered with letterpress in conveying information and commentary about current events.

Herbert Ingram

That pictorial journalism took this particular form at this historical moment owed much to the frenetic energy and finely honed entrepreneurial instincts of an obscure provincial tradesman named Herbert Ingram. Both the provincialism and the involvement in trade proved crucial to shaping the vision that Ingram brought to the founding of The Illustrated London News. A stout, square-built man with bulging blue eyes, shambling gait, coarse manners, and a mercurial temperament, Ingram was a shrewd observer with a keen instinct for the main chance. His reserves of energy were as boundless as his ambitions; once possessed of his one big idea, he would not rest until he had done everything in his power to carry it out.

Born of a Lincolnshire family, Ingram lost his father in infancy and after a perfunctory grammar-school education was bound apprentice to a printer. After serving that apprenticeship, he worked as a journeyman printer in London for two years in the early 1830s until he had saved enough money to start a printing-office and newsvendor shop in Nottingham in partnership with Nathaniel Cooke. Shops like Ingram’s and Cooke’s did a bit of everything—job-printing of handbills, selling patent medicines, handling the latest cheap newspapers—and in fact it was this opportunistic mix of business that made Ingram his first serious money and gave him the idea that would change journalism forever.

Like hundreds of other small shop-owners around the country, Ingram had signed up to be an “agent” for Morison’s Pills, a heavily promoted cure-all that brought its inventor a tidy fortune until the mid-1830s, when people started conspicuously dropping dead from its corrosive properties. Sensing an opening, Ingram decided to launch a cure-all pill of his own. Drawing on an old Shropshire legend about a man named “Old Parr” who lived to be 152 years old, he had a Manchester druggist come up with “Parr’s Pills,” good for every ailment from heart problems to insomnia to constipation, and said to be compounded from instructions left by Old Parr himself. Commissioning a fabricated “life” of Old Parr and an equally fanciful engraved portrait to promote the pills, he soon had his own network of agents throughout the country, and used his new earnings to set up an office in London at Crane Court, in the heart of London’s publishing center, to manage the enterprise.

A New Vision

From this new base of operations, Ingram was poised to embark on what would become the work of his life, inspired by bringing together a couple of observations about the news trade he had got to know so well as provincial vendor. Ingram had noticed that whenever a cheap paper like The Weekly Chronicle carried a woodcut engraving, as it did for weeks during the trial and hanging of the notorious Camberwell murderer Jonas Greenacre in 1837, sales of those numbers skyrocketed well beyond the paper’s normal circulation. The other lesson he drew from his news-vendor experience was that the country customer always asked, not for this or that paper by name, but for “the London news.” What would be the effect, he imagined, of a paper that, instead of carrying a few pictures now and then, carried a great many pictures every week, tied to events in which there was already intense public interest, a paper that already had both “London” and “News” in its title? At first, Ingram appears to have considered a paper along the lines of what later became The Police Gazette, focusing on sensational crime stories; just as he had gone Morison one better by inventing and marketing his own pill, he was confident that he could beat sensation-mongers like The Weekly Chronicle at their own game. But he soon concluded, or was persuaded, that a loftier and more ambitious view of the project, while riskier, would stand an even greater chance of success.

The time was ripe. The previous summer had seen the appearance of Punch, a lavishly illustrated comic weekly that was nevertheless a respectable, family publication, free of the gross caricatures and salacious innuendo that had long been associated with the satirical press. Punch’s success seemed to open the way for cheap illustrated papers that were not only respectable but also topical, for along with its well-worn puns, Punch revelled in the kind of satire that took the news of the week as its theme. Ingram was closely acquainted with the Punch circle: Ebenezer Landells, one of its founders, was recruited as both engraver and artist, while the magazine’s editor, Mark Lemon, proved a trusted advisor to Ingram as he planned The Illustrated London News.

Success in the Marketplace

Still, formidable obstacles remained. No publisher had ever before tried to organize engraving on this scale or at this speed. Ingram rushed to find as many artists and engravers as possible, and set them to work. As it was, for the first number, Ingram was obliged to resort to gimmicks – with no artist in Hamburg, for example, a print of the town skyline was borrowed from the British Museum from which a copy was hastily drawn, with smoke and flames added. The marketing campaign for the inaugural issue took the town by storm: two hundred men wearing sandwich boards (each with one letter of the announcement) paraded up and down the major London avenues in advance of its appearance, at one point completely encircling the Bank of England. To edit the new paper, Ingram called upon the talented, hard-drinking F. W. N. Bayley (known to his peers as “Alphabet” Bayley for his unreasonable profusion of forename initials), who proclaimed in a florid address to the public the Illustrated’s determination “to keep continually before the eye of the world a living and moving panorama of all its actions and influences.” Ingram’s greatest recruit was artist John Gilbert, whose meticulous yet fluid style would forever after define the “look” of The Illustrated London News, and whose astonishing speed and deftness – it was said that he could make any full-page drawing requested, directly on the woodblock, within an hour, while the messenger waited – would grace the paper with an estimated 30,000 drawings over the following thirty years.

The success of that first number passed into legend: 26,000, a spectacular first-week sale for a new publication. There was a falling-off for the next number or two, yet sales soon bounced back and began climbing steadily, thanks in no small part to Ingram’s genius for marketing. Particularly successful was the promotional offer, new to the trade, announced in the inaugural issue: those who subscribed to ILN for six full months would receive, at the end of that time, a large-format (‘coliseum’) print of London. No such incentive had ever been offered to magazine or newspaper subscribers before, and no engraving of this size and complexity had ever been attempted. Antoine Claudet the photographer was hired to climb the Duke of York’s tower and make a series of images that could be fitted together and used to sketch a panorama of the city, looking north and south. Artist C. F. Sargent then made the drawing onto sixty boxwood engraving blocks, each about 5” square, that had been drilled and fitted together with long brass bolts to make one huge block, after which eighteen men, working under the direction of Ebenezer Landells, painstakingly engraved the drawing. The resulting 3’ by 4’ print was a fantastic success, universally praised, that well rewarded the hopes of both subscribers and the proprietor. By December of 1842, circulation had almost tripled, to 66,000.

The start-up and expansion costs associated with the paper were enormous, and at some point in these early years, Ingram was obliged to borrow £10,000 from his brother-in-law and publisher, William Little. The investment paid off handsomely, and the paper went from strength to strength as Ingram forged boldly ahead, assembling a staff and a production system capable of gathering the most far-flung news, adding new departments and features, experimenting with new printing presses and reproductive processes, acquiring his own paper mills, and trying out one promotional idea after another. When a new Archbishop of Canterbury, John Bird Sumner, was officially enthroned in 1848 in a newly elaborate ceremony, Ingram devoted lavish coverage to the event and sent a free copy of the paper to every Anglican clergyman in the country, a daring stroke that secured a vast increase in circulation. The ILN proved to be a boon to artists and sellers of art, as well, with painters clamouring to have engravings of their works included in the paper, while engravings of selected paintings at the annual Royal Academy exhibition were a perennially popular feature.

Mid-Victorian Triumphs

The press of events in the 1840s and 1850s also contributed to the soaring popularity of a paper that could show as well as tell. The Revolution of 1848 in France that saw the abdication of the king and the birth of the Second Republic amid the barricades of Paris so roused the British reading public that demand for the ILN skyrocketed, and poor William Little was pelted in the street with fistfuls of flour by frustrated readers and newsvendors over delays in supplying them with copies. The Illustrated’s coverage of the Great Exhibition of 1851 was a triumph, beginning with its advocacy of Joseph Paxton’s brilliantly original designs for what came to be known (thanks to Douglas Jerrold in Punch) as the Crystal Palace. The paper’s publication of those designs allowed Paxton to circumvent the doubters on the exhibition’s selection committee by taking the matter directly to the British public, whose universal and enthusiastic acclaim made the choice a foregone conclusion. The week the Exhibition opened, The Illustrated London News sold 100,000 copies. Special supplements, with fold-out engravings of the building and its contents, associated the paper even more closely with an event that celebrated British national achievement. The following year, the ILN’s extraordinarily lavish coverage of the Duke of Wellington’s funeral likewise made it a central participant in the construction of the aggressively proud national identity that emerged in Britain in the mid-Victorian years. Supplements—prominently labeled “Gratis”—abounded, issued to mark one or another notable event, while the paper’s profusely illustrated accounts of the treasures unearthed (and brought to England) by Henry Austen Layard in his excavation of Nimrud (1845-51) (often referred to as ‘Nimroud’, for an example of the discoveries see 16 Dec 1848) presaged a near-obsessive devotion to the subject that would grow even more pronounced in the following century. Another bold innovation was the introduction of colour: the Christmas 1855 issue contained the first colour pictures ever printed in an English newspaper, beginning a Christmas tradition that would prove wildly popular with readers and advertisers alike.

Becoming an Institution

Befuddled by drink and harassed by debt, F. W. N. Bayley had abandoned his post to sub-editor John Timbs by 1848, and was formally succeeded as editor in 1852 by Charles Mackay, who had joined the paper after a stint as editor of The Morning Chronicle. Best remembered today as the author of Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds (and perhaps also as the father of best-selling Edwardian novelist Marie Corelli), Mackay was one of the finest all-round journalists in London, and he helped to assemble a staff that by the end of the decade numbered some 160 writers, artists, engravers, and editors. In 1855, at the height of the paper’s exhaustive coverage of the Crimean War (for an example of weekly coverage see ‘Sketches in the Crimea’ 10 February, 1855) and the year that the despised stamp duty on newspapers was at last abolished, circulation reached 130,000; a mere seven years later, boosted by coverage of the wedding of the Prince of Wales, sales had topped 300,000. A key advantage enabling this kind of growth was the virtual absence of serious competition until the founding of The Graphic at the end of 1869. Ingram’s huge early investment, and continual reinvestment, made it difficult for others to keep pace; despite a promising start and brilliant contributors, Henry Vizetelly’s Pictorial Times, begun in 1843, was out of business by 1848. Ten years later, Ingram, ever the resourceful businessman, dealt with the more serious threat of Bogue and Vizetelly’s Illustrated Times by the costly but simple expedient of buying the rival paper.

Tragedy

Unsurprisingly, the success of The Illustrated London News brought its proprietor enormous fame and wealth. On the strength of both he was able to enter Parliament, where he lobbied vigorously against the taxes on paper that kept newspaper prices artificially high, and busied himself with improvement schemes for Lincolnshire. Yet for all his success, Ingram’s business and personal affairs were tangled and worrisome, and after some rash speculations, a hint of financial scandal, and the withdrawal of William Little as publisher following a bitter family falling-out, Ingram decided to leave the country for a time by taking his teenaged eldest son on a tour of America. In the early morning hours of September 8, 1860, the Lady Elgin, the crowded Lake Michigan steamer on which the Ingrams were traveling, was rammed by a lumber schooner and broke up in rough seas north of Chicago. In this, the greatest open-water disaster in the history of the Great Lakes, almost 400 passengers lost their lives, including the ILN’s founder and his son. His newspaper did a characteristically thorough job of covering the tragedy (see "Loss of the “Lady Elgin”….", 29 September, 1860)

Artists

In the decades that followed Ingram’s death, the system that he had put in place continued to thrive and expand under the watchful eye of his widow, Anne Ingram, a woman of considerable business acumen, with the help of such stalwarts as publisher George Leighton, editor John Lash Latey (who had succeeded Mackay), and art editor Mason Jackson, until her sons William and Charles were old enough take a hand in managing the enterprise. Clearly central to that system was the artistic staff of the paper, which included both those who worked in a kind of factory in the ILN’s own studio in London and those who travelled as special correspondents, sending back sketches to be transformed by the studio staff into finished drawings on the block, ready for engraving. In both cases, the staff was so large and diverse that the paper was able to make use of a wide variety of special skills. Lucien Davis, for instance, was particularly good at capturing the sheen of silk and satin, and so was dispatched to cover fashion and fancy dress balls, while artists such as Herbert Railton and his student Holland Tringham excelled with landscapes and old buildings. Similarly, Louis Wain and Stanley Berkely specialized in cats and dogs (respectively), whereas T. Scott, before photography came to be used, was the paper’s main draughtsman of portraits. But undoubtedly the most glamorous role fell to the “special artist correspondent.” Six artists covered the war in the Crimea in the 1850s, while five were sent in 1870 to bring readers scenes from the Franco-Prussian War. The work carried obvious dangers; one correspondent in France in 1870 was obliged to eat his sketches to avoid being shot as a spy. In the high noon of the British Empire, such correspondents were dispatched to the far corners of the globe to cover what historian Byron Farwell has called “Queen Victoria’s little wars.” Short and bald, with mutton-chop whiskers and a shrill voice, artist Melton Prior proved the most ubiquitous of these correspondents in the last third of the century. Making his name in the Asante campaign in 1873, Prior claimed to have covered twenty-six wars for the paper in the course of thirty years.

Writers

Yet it would be a mistake to attribute the success of the ILN, or indeed its importance to historians, merely to the illustrations. Those “48 columns of news” in the first issue were almost as great a source of pride as the engravings that accompanied them, and indeed it is the complex relationship of text to image that makes the ILN such a fascinating object of study today. Readers were treated to full write-ups of political news, as well as editorials (“leaders”) on topics of the day, and detailed descriptions of pageants, battles, buildings, inventions, archaeological discoveries, disasters, elections, and much else. Obituaries, often accompanied by a portrait, were a much-prized feature. Sometimes these were specially commissioned; on the occasion of the death in 1865 of Lord Palmerston, the last British prime minister to have died in office, veteran journalist and ILN leader-writer Shirley Brooks was brought in (and paid a munificent £18) to furnish a full-scale memoir that echoed the Wellington funeral coverage in its celebration of the essential Englishness of this famously jingoistic statesman. Fiction, too, became an early staple, initiating a feature that would fully blossom later in the century, when the paper carried stories and novels by such well-known authors as Rider Haggard, J. M. Barrie, William Black, Henry James, and Thomas Hardy.

Columns

The introduction of columnists on various topics proved one of the keys to the paper’s continued popularity. Angus B. Reach, a dazzlingly prolific journalist from Inverness, pioneered the breezy, insider, arts-and-letters gossip column in 1850-51 with “Town Talk and Table Talk.” (It was here, for instance, that the reading public first learned that the mysterious initials “PRB,” adopted by a controversial group of artists, stood for “Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood.”) See The ILN Celebrities and Gossip essay by Sally Mitchell for a dedicated paragraph on this column. Under a variety of titles, this sort of column delighted readers for decade after decade, kept lively and topical by such able writers as Peter Cunningham, Shirley Brooks, and (for thirty-five years) the irrepressible polymath and man-about-town, George Augustus Sala. As “Our Note Book,” it soldiered on into the twentieth century under such stalwarts as G. K. Chesterton and Arthur Bryant. (see The ILN and Our Note Book essay by Dr Julia Stapleton) Always in the forefront in its coverage of the ceremonial aspects of politics, the paper also offered gossipy views of the personalities and tactics of the House of Commons with John Latey’s “Silent Member” pieces. In over 1500 columns between 1886 and 1918, “Ladies Notes” by pioneering feminist Florence Fenwick Miller provided an influential sounding-board and a strikingly progressive voice on a wide variety of women’s issues. Dr. Andrew Wilson held forth on the latest news from scientific circles, with special emphasis on natural history, in his “Science Jottings” (1890-1912). No feature in the paper could boast a more devoted following than the column presided over from 1845 by the brilliant, caustic, and frequently infuriating chess master Howard Staunton. Featuring illustrated chess problems, analysis of recent matches, and often tartly astringent replies to correspondents, Staunton’s column came to exercise a powerful worldwide influence for almost thirty years.

Into the Twentieth Century

The Illustrated London News continued to innovate and to soar in popularity well into the twentieth century. Under the sixty-year editorship of Herbert’s grandson, Bruce Ingram, which began in 1900, the paper would cover two world wars and provide its readers with uniquely lavish accounts of such unforgettable stories as the sinking of the Titanic. and the opening of King Tutankhamen’s tomb (see the first special number 3 February, 1923). But like its Victorian forebear, the modern ILN would continue to make its most characteristic contribution to the cultural life of its time in the steady, unspectacular weekly coverage of events large and small, within Britain and around the world. Never a simple “reflection” of its times or of public attitudes, the paper was deeply involved in shaping both. The opportunity we now have to explore the illustrations and the letterpress as they originally appeared in those pages will inevitably deepen our understanding of the world’s first illustrated paper, and of the society that produced and sustained it.

CITATION: Leary, Patrick: "A Brief History of The Illustrated London News." Illustrated London News Historical Archive 1842-2003. Cengage Learning, 2011