Introduction: The ILN’s Record of the Remaking of the British Museum

The first decade and a half of the ILN’s life coincided with the slow, piecemeal process by which the British Museum took its modern shape (finally fully opening its new doors in 1857), and that transformation was tracked closely in the pages of the paper. Part of the change was essentially a matter of space and architecture: moving the museum’s holdings out of Montague House, which the museum/library (the British Library and the museum, it will be recalled, shared quarters until their separation in 1998) had long outgrown, and into the familiar Robert Smirke edifice it still occupies today. The ILN illustrated the transition, showing readers the new building in 1844 (along with a critic’s complaints about it; (“The New British Museum”, 13 January 1844), a comparison of old and new in the midst of the transition a year later (“The British Museum”, 27 September 1845), and views of each new room as it opened to visitors (see, for example, “Xanthian Room, British Museum”, 15 January 1848, or “The New Reading-Room and Libraries of the British Museum”, 9 May 1857).

But the deeper change in the institution was more than just architectural. It was, first of all, the transformation from a library with a few odds and ends (those vases Lord Hamilton brought from Naples, the collections Captain Cook made in the Pacific), to a showcase of the collected masterpieces of human civilization with a library tucked into its midst. This transition began, of course, before the ILN was there to report it – think of those much-debated hunks of marble Lord Elgin hauled back from Athens – but in the period of the museum’s surface remodelling, it can be tracked clearly in the ILN’s close attention to the expansion of the collection. Just in the first years of the journal’s existence, it noted new zoological specimens from Antarctica (for natural history was still a part of the museum until their removal to South Kensington in 1880; see “Additions to the British Museum”, 24 February 1844), casts of some Parthenon friezes that Elgin missed (“Additions to the British Museum”, 8 March 1845), classical sculpture from Halicarnassus (“The Budrum Marbles in the British Museum”, 30 January 1847), Peruvian and Mexican antiquities (“Additions to the British Museum”, 3 April 1847), and new Assyrian finds (“The Nimroud Marbles at the British Museum”, 28 August 1847), to list only the most notable examples (among the less notable additions was a box Lady Holland received from Napoleon himself). The rapid expansion of the museum’s non-book collections – by this point a quite deliberate process as opposed to an accidental accumulation – constituted a redefinition of the museum itself.

The accompanying character of the museum’s constituents and the transformation of the British Museum from a gentleman’s library to a public museum is more difficult to trace in the pages of the ILN, but the story is there. A piece on “Easter Monday at the British Museum”, 29 March 1845, opens with an illuminating snatch of verse: “As motley crowd was gather’d there/ As ever throng’d a show.” A short bit about “Visitors to the British Museum”, 1 March 1851 records the steady increase in visits, from 685,613 in 1844 to 1,098,863 in 1850 (and attendance in the year of the Great Exhibition would massively swell). And by the time F. Smith contributed his illustration “Holiday Time: British Museum”, 12 April 1873, the museum’s halls are so crowded it looks like a party.

The Birth of the Museum

The British Museum would continue to grow and change, and the ILN would continue to track its shape-shifting course. Indeed, in the Christmas number for the year 2000, the paper would offer a full feature on the remodelled Central Court, made possible by the library’s removal (“Britain in a New Light”, 4 December 2000). But the point is not that the ILN was especially obsessed with the British Museum; indeed, it spent almost as much time lingering over the Louvre (224 articles indexed over the paper’s full run, compared to 369 for the British Museum). Rather, the attention to the British Museum illuminates a broader issue: that the coming of the ILN coincided with the invention of the true public museum, a process that illustrated journalism was particularly well suited to cover.

Although a few anomalous examples can be traced further back – Florence’s Uffizi galleries were open to the public, at least in some limited way, from the sixteenth century on, and Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum opened in 1683 – the museum is essentially a product of eighteenth-century Enlightenment thought, paralleling the conceptual framework of Denis Diderot’s Encyclopédie in two critical respects: in the project of encapsulating human knowledge in a defined space (a book or a building), and in the democratizing notion that such knowledge be made accessible to any reasoning being. This Enlightenment impulse, in combination with heightened national consciousness (the national chauvinism so critical to the development of specifically national collections), provided the impetus for the foundation of a range of new museums across Europe in the last decades of the eighteenth century. The British Museum, for example, opened in 1759; the first Royal Academy show was mounted in 1769, and they opened galleries in Somerset House in 1780; and the first calls for the formation of a National Gallery in Britain came in 1777 (although the collection would not be realized until 1824).

But it would take a broader shift, political as much as cultural, to turn such spaces into genuine public territories. It is thus not coincidental that the opening of the Louvre to the public came in 1793, in the midst of the French Revolution. But to remake the essentially private aristocratic collections, the cabinets of curiosity and noble or royal art collections of the early modern era, into the modern public museum, would take time: the time needed to fashion a fully autonomous public sphere, or, to put it another way, the time needed for British and Continental elites to endorse the inclusion of a broader public in the museum programme. In Britain, the trend is clear in the early decades of the nineteenth century: the Dulwich Picture Gallery, in Sir John Soane’s pioneering purpose-built facility, opened in 1817; Soane’s own house museum, showcasing both his eclectic collections and his architectural skill at displaying them, opened to the public in 1837; building on the new British Museum commenced in 1823, and the National Gallery, as noted, was created in 1824; Queen Victoria opened Hampton Court and its collections to the public in 1838; the London Zoo, a museum of another sort, opened to the public after decades of private access in 1847. But as late as 1848, as Edward Miller notes in his history of the British Museum, museum officials responded to the presumed (but utterly illusory) threat of Chartist demonstrations by mounting an armed guard on the collection (That Noble Cabinet: A History of the British Museum [1974], 167-71). It was the Great Exhibition of 1851, really – with its deliberate courting of the respectable working class (through “shilling days” and other devices, as well as with its swelling of the museum-ready population of the city – that changed the terms of museum access for good. And the South Kensington Museum (opened in 1857) built from the profits of that exhibition continued the programme, pioneering gas lighting in galleries to allow evening hours and insistently providing free days and evenings to develop a broader base.

Promoting the Museum Movement in the ILN

Debuting in the midst of these developments in 1842, and featuring illustrations perfectly fitted to showcase new museum’s collections and modes of display, the ILN was especially well positioned to participate in the shaping of the museum as a new public space. The journal’s opening address was curiously silent about this range of coverage: “In the field of fine arts – but let the future speak, and let us clip promise in the wing. We have perhaps said enough” (“Our Address”, 14 May 1842). But they were quick to redress the gap, covering its first Royal Academy exhibition in the same issue (“Fine Arts”), and an illustrated tour of the following year’s show (“The Exhibition of the Royal Academy”, 20 May 1843). In 1843, the ILN also noted an addition to the National Gallery collection (“Van Eyck’s Picture in the National Gallery”, 15 April 1843) and detailed the nature of the collections at the new Royal Museum in King’s College (“Opening of the Royal Museum at King’s College”, 1 July 1843).

Such close attention to museums and their collections would continue to feature in the ILN’s pages in subsequent years. As noted, the paper closely tracked the gradual unfolding of the British Museum and its collections. It routinely apprised readers of new National Gallery additions (featured in 306 articles over the full run). Significantly, given South Kensington’s role in shaping the modern museum, the ILN closely followed the development of the museum complex there, from the opening of the temporary ironclad building (dubbed by critics the “Brompton Boilers”) in 1857 (see “The South Kensington Museum”, 27 June 1857) onward through the gradual augmentation of the collections and the establishment of permanent facilities (the new buildings lavishly covered in “New Buildings of the South Kensington Museum”, 29 September 1866, and the collections to that point surveyed in “The Art Collections at the South Kensington Museum”, 7 August 1866). A sense of the popular success of the project can be garnered from packed crowds shown in the illustration “The South Kensington Museum on Whit Monday”, 3 June 1871). The ILN attended not only to the South Kensington Museum (now the Victoria and Albert), but to the wide range of other facilities the proliferated on the site: the Architectural Museum, the relocated Schools of Design (later redubbed the Department of Science and Art), the gardens of the Horticultural Society, the initial version of the National Portrait Gallery, Royal Albert Hall, the Indian Museum collections, the Science Museum and its attendant schools, and the Natural History Museum, among others.

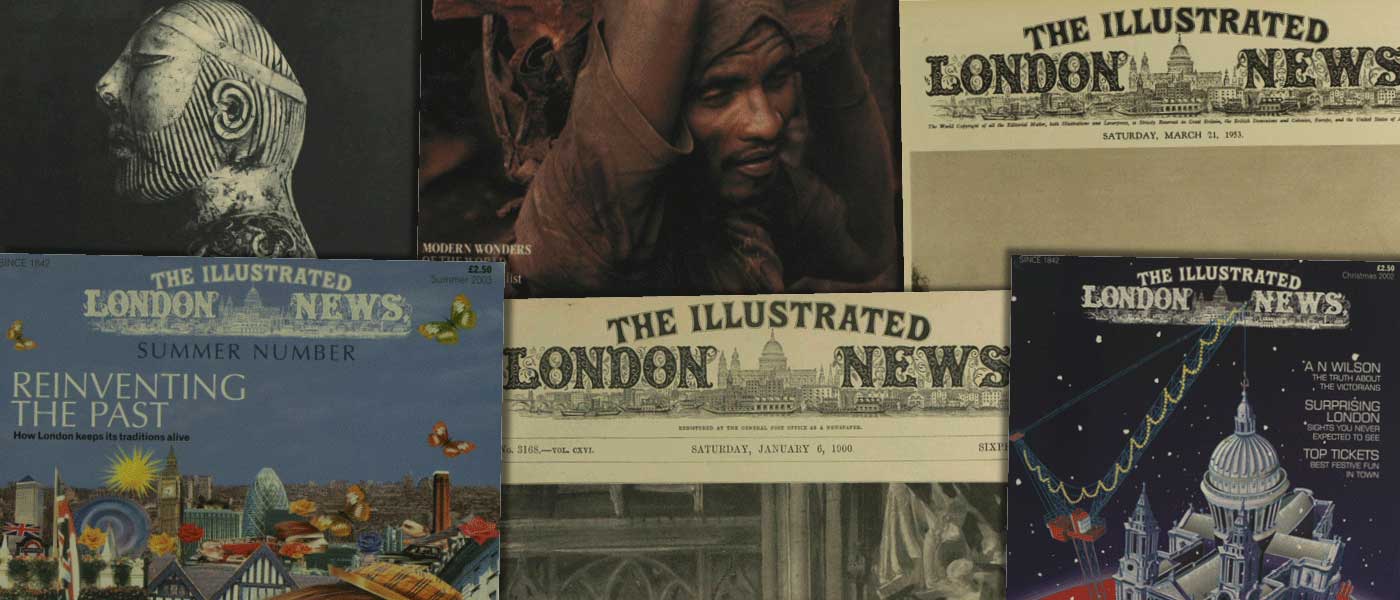

The ILN and the Twentieth-Century Museum By the dawn of the twentieth century, the public museum was firmly established. But the focus of museum collections and popular attention to them shifted over time, reflecting broader political, social, and demographic trends. Old favourites still got covered – the ILN offered its readers a view of the new buildings at South Kensington in 1903 (“The New Victoria Museum of Science and Art at South Kensington”, 23 May 1903) and the expansion of the British Museum in 1907 (“The British Museum’s Huge Extension”, 29 June 1907) – but new themes and interests can also be noted. The London Museum, for example, attended more closely to the domestic realm of the past (as evidenced in “London’s Museum of Her Own History in a New Home”, 21 March 1914). As World War I drew to its long-awaited close, collection of artefacts for a new war museum began (“For the National War Museum: Relics from the Front”, 20 October 1917). More specialised museums, like the International Stage Museum, opened their doors (“The New Stage: The Exhibition of Theatre Craft”, 3 June 1922). And even high art bowed to more democratic instincts, as when the Tate showcased workers’ art (“A Flowering of Art in the East End: Workers’ Pictures to be Shown at the Tate Gallery”, 29 December 1928). Beginning in 1973, the ILN initiated a “Museum of the Year” award, and the changing focus of museumology and of the paper’s interests can be tracked through the award’s grants, from that first year’s recognition for the Museum of Lakeland Life in Kendal (“Museum of the Year”, 26 May 1973) to the Manchester Museum in the award’s final year (“Museum of the Year 1987 Award Winners”, 25 July 1987). And in the ILN’s final years, it took note of the new trends in museum design, as with Norman Foster’s redesign of the British Museum’s Central Court (noted above), I. M. Pei’s Louvre pyramids (“The Louvre Reborn”, 7 June 1993), or the opening of the Tate Modern (“Lars Nittve, Director, Tate Modern”, 4 December 2000).

Finding the Museums in the ILN Archive

Locating museum coverage in the ILN is fairly straightforward: searching under museum will get most of what you need, supplemented by gallery (to cover the National, National Portrait, and Tate) with the note that “gallery” will also produce a host of less relevant results. This can be supplemented further by searching exhibition to garner the paper’s very routine coverage of individual shows that are often not indexed even under museum name (but again with lots of stray hits). In the later years of the publication especially (from 1988 on), articles titled simply “Exhibition” or “Exhibitions” were regularly featured. For more precise, less-likely-to-stray searching, use the specific museum name.

The character of coverage in the ILN is two-fold, with the two terrains never quite distinct: strictly reportorial pieces (new acquisitions consisting of this and that, the new building looks like this) and critical reviews. Broadly speaking, nineteenth-century coverage seldom offered straightforward reviews, but often folded critical comment into the presentation, sometimes through the device of quoting other critical comments. By the early decades of the twentieth century, review and straight reportage are more often separated, although never quite entirely. And even in the straight reportage, critical insights can be gleaned. A 1929 pictorial piece, for example, comparing photographs of the Parthenon frieze with drawings of the same pieces when acquired (“Decaying Sculptures on the Parthenon”, 18 May 1929), puts the lie to the British Museum’s routine reason for refusing to return the sculptures, that keeping them in London is the best way to ensure their survival.

CITATION: Prasch, Thomas: "The Illustrated London News and Museums." Illustrated London News Historical Archive 1842-2003. Cengage Learning, 2011